Intra-Africa Humanitarianism: A Qualitative Case Study of the Somali Business Community in Zambia

Sahra Ahmed Koshin, University of Nairobi

This paper examines the participation of the Somali business community in Zambia in relief and humanitarian assistance to Somalia during times of emergencies, crisis and disasters. The study examines the unique experiences of the Somalis in Zambia, their connection to Somalia, how they express their urgency in relief provision, their giving practices, how they demonstrate solidarity, and their motivations for sending support. The paper also explores the disaster relief campaigns and assesses the institutions used in sending support, the types of assistance they mobilize, and the modes of communication they employ vis-à-vis the historic and evolutionary origins of the Somali business community in Zambia and their wider implications.

The first group of Somali migrants arrived in Zambia in 1966 as truck drivers, and the other groups of Somalis moved to Zambia due to the political situation in Somalia in the early 1990s and the search for economic opportunities. Many Somalis had ventured into entrepreneurship with businesses like; hotels, oil business, transportation, and mobile money transfer businesses. The respondents interviewed were aged between 36 and 68 years of age from Ndola and Lusaka cities. The interviewees had lived in Zambia between 10 and 38 years and they had a strong connection with Somalia with frequent visits to Somalia. The majority (8) of the respondents interviewed were women.

Somalis in Zambia are instrumental in sending humanitarian assistance to communities and families affected by emergencies in Somalia. Remittances and cash transfers were identified to be the main contribution to Somalia. The Somalis in Zambia use informal channels in sending money because of the low cost, although they have more recently embraced other fundraising digital technologies such as crowdfunding platforms like go fund and just giving. They also use social media outlets to communicate and access information on Somalia such as WhatsApp groups, Paltalk groups and Facebook. Further still, it was discovered that Somali women have been actively engaged in doing business despite the social and cultural barriers.

The study found that the motivation to give is driven by religious and social factors. Female migrants interviewed cited marriage reasons and the search for economic opportunities as the main factors that inspired them to move to Zambia. The findings from this study could help the Zambian government in documenting revenue mobilization within the Somali communities. The Somali government, specifically the government of Puntland, could use this connection to promote business opportunities.

1. BACKGROUND

Ever since the collapse of the Somali government in 1991, Somalia has experienced a series of humanitarian emergencies ranging from conflicts instigated by armed groups, conflicts by clan militias, famine, and drought (DEMAC, 2021). These factors have driven many Somalis out of Somalia. The United Nations (2015) on Somalia Migration Routes in the East and Horn of Africa, cited by the Maastricht Graduate School of Governance, asserts that there are over 2 million Somalis living outside Somalia. The main countries of destination include; Kenya, Ethiopia and followed by other African countries. Outside of the Africa, Europe comes first (14.01%), then Asia (13.16%) and North America (8.25%) (MGSoG, 2017).

Zambia is one of the African countries hosting Somali communities. Though there is no official data on the number of Somalis in Zambia, it is estimated there are over 5000 Somalis specifically in the cities of Lusaka and Ndola. The Somalis in Zambia are involved in business and trade, the transportation sector, hotels, restaurants, and the oil and gas sector. The Somali community in Zambia was selected because of the growing number of Somalis in the country as well as the strong historical ties and current ties it has with Puntland. These ties include cultural, religious/spiritual, business, development and also humanitarian ties.

There is increasing recognition of the role that the Somali diaspora plays in responding to humanitarian crises (Kleist 2008, Horst 2008, Hammond 2011, et al.). Different authors have approached this from different angles and provided insights into how diaspora humanitarianism functions. A significant contribution has been an increased understanding of Somali diaspora humanitarianism in complex crises and why people give to the cause. Horst (2008) focused on the neglected role of assistance provided by refugees within the framework of international aid practices in long-term refugee camps. The author’s main argument is that refugees need to be acknowledged as both assistance receivers and as providers of aid, balancing the power dimensions implicit in the act of giving. The Federal Government of Somalia (TFG) is currently making attempts to harness the benefits of the diaspora community in relief extension and economic development of Somalia. The Federal Government has established the department of Diaspora Affairs at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to deal specifically with diaspora engagement. However, an institutional framework to integrate Somali diasporas into a wider national development process does not exist.

The inclusion of Somali diaspora communities in humanitarian relief support has received wide coverage and attention in the last 20 years (Kleist 2008, Horst 2008, Hammond, 2011, et al.). The diaspora in Africa have received little focus. Despite the enormous contributions of these Somali diaspora communities in humanitarian assistance, the potential of this group is yet to be explored sufficiently. In sub-Saharan African countries, data on the scale of Somali diaspora humanitarianism within the African continent is still inadequate. It is, however, broadly acknowledged in Somali society, based on the increasing visibility of businesspeople in the diaspora, that there has been a steady increase in their involvement in the past few years, particularly during disasters and crises. This increase marks a new phase of diaspora engagement in Somalia. Remittances sent by this group as well as by the globally dispersed Somali diaspora continue to provide vital support to families in Somalia.

Much of the history of Somali migration in Africa has been told through the lens of refugees whose experiences are driven by civil war and challenging economic conditions, such as drought and famine (Bakewell, 2016). However, Somali mobility in Africa is shaped not only by both regional crises but by opportunities (Iazzolino & Hersi, 2019). To date, there has been inadequate empirical research conducted on the migration patterns of Somalis on the African continent and the entrepreneurship of Somali business migrants in Zambia. Given this, this research seeks to respond to this lack of knowledge and understanding of the migration and entrepreneurship models of Somali migrants in Zambia.

Why Zambia?

I selected Zambia because it was among the first African countries to host Somalis in 1966. This group further invited their families. This group was followed by other Somalis in the early 1990s that moved out as a result of the Somali civil war and the government breakdown. This increasing number of Somalis in Zambia and their contribution to Somalia through humanitarian assistance, are another reason why Zambia was selected. The existing business links between the Somalis in Zambia and those in Somalia create interest to explore the motivation to understand this relationship.

Zambia stands out from other Somali migrant hosting countries in Southern African, for instance in South Africa. Somali communities in Zambia were established in the country as early as the mid-1960s. Some came there as expatriate drivers to work in Zambia, as came as political dissidents who fled the country under the Mohammed Siyad Barre regime because their lives were in danger. Both groups settled thee and begun a business enterprise that spanned from transport to oil and gas, real estate, to retail businesses and so on and so forth. Somalis in South Africa are a new community which was established in postapartheid South Africa when the county embraced democracy in 1994 and Somalia’s state collapsed in 1991. Notwithstanding, the Somali business communities in South Africa has also attracted scholarly attention see for example others, Omeje and Mwangi (2014), Tengeh (2016), Thompson (2016).

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

The study adopted a qualitative case study approach as it aimed at exploring the in-depth understanding of respondents on their role in humanitarian assistance extension to communities in Somalia affected by emergencies and disasters. The study used descriptive data as it would respond to their natural setting (Yin (2017). The primary data was collected over three months from 19th March 2021 to 30th May 2021. The study embraced Key Informant Interviews, Focused Group Discussions (FGDs), field observations, and archival data. The researcher interviewed ten key respondents selected through snowball sampling in Lusaka and Ndola towns in Zambia.

The respondents included company owners and business owners. Snowballing was used as the respondents would lead the research to other respondents with the required information needed for the study. Focus group discussions targeted business owners, businesswomen, and women’s groups were involved in the study. Selective snowballing was used because this type of sampling was found to be conducive to this study of this kind, which involves social networks and transnational practices across communities. The study used different entry points to create snowballs, obtaining diverse viewpoints. The respondents included senior Somalis some of whom have lived and worked in Zambia for over 50 years.

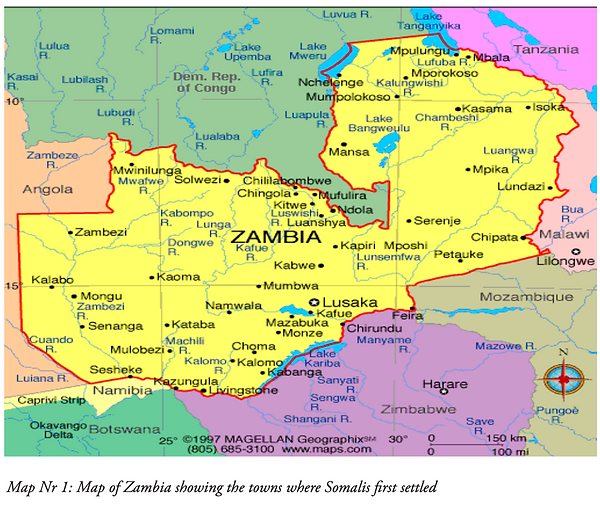

Since 2020, the researcher has been observing the interaction between the Somalis in Zambia and those in Somalia and other parts of the world on social media and through online forums to assess how advocacy and resource mobilization for disaster relief is initiated. The analysis categorized data to classify, summarize and tabulate it into themes guided by the research objectives. The locations in Zambia were selected due to the following reasons. Ndola was selected because it is the first town in Zambia where the first Somalis who arrived resided, particularly in a place called in Somali ‘Gotka’, meaning ‘the deep hole’ just on the outskirts of the town. Ndola is a city located in the Copperbelt Province of Zambia and the place where most Somalis drivers worked. On the other hand, Lusaka was selected because it is the Zambian capital with many business opportunities. As the Somalis increased in number and a good number moved to Lusaka and eventually to many other places in Zambia. In these towns, the historical presence of the Somalis in Ndola can be seen and felt. Some of the oldest elderly Somalis live in this city, and some of the garages and houses they bought to live and work, and the trucks they used then, still exist.

3. EMPIRICAL RESEARCH RESULTS

Characteristics of the respondents

To explore the opinions of participants, the researcher engaged 10 participants (6 female and 4 male). While selecting these participants, the researcher considered gender, age, location, and the length of their stay in Zambia. Almost all the participants interviewed were born in Somalia. Six of the participants interviewed were married, 2 participants were single, and 2 participants were widowed. As far as the age of respondents is concerned, the youngest participant was aged 29, while the eldest was aged 61. The majority of the participants involved in this study were in the 36-to-40 age group. The researcher involved participants from two major cities namely; Ndola and Lusaka. These two cities were identified as the main areas of residence of the participants and also the first locations where the Somalis settled when they first came there in the 1966.

4 of the 10 participants involved were from Ndola, while 6 participants were selected from Lusaka. Three participants involved in the study had primary education, 2 participants had a diploma, and another 2 participants had a university bachelor’s degree. In terms of education, this section explored the level of education attained by the participants. The highly skilled and educated and the less educated Somalis make significant contributions to their motherland Somalia. Nine of the respondents involved in the study were born in Somalia and the findings further discovered that the participants had lived in Zambia for over 10 years and other participants had lived for over 30 years. The participants also revealed that they visit Somalia at least once a year to meet their family members.

The Somalis in Zambia – Who are they and why did they come to Zambia?

The Somalis businesspeople who took part in the study revealed how they entered Zambia and the activities they conducted that led to their business success as well as the connections they have with Somalia. One respondent revealed “I came to Zambia in 1970 to look for a job as a driver at OHAN Transport Company. Later my wife and children joined me. “I have been here ever since, but I do travel regularly to the wadankiii (homeland).”

Zambia gained independence from Britain in 1964, and since the country was landlocked, it needed help in building the nation. The Zambian infrastructure at the time was very bad and the roads were dangerous to the extent that they were called “the Hell Run”. 1 The government of Italy responded to the plea for assistance with the delivery of Fiat trucks which were then driven by the Somali drivers. In a focus group discussion with some of the first members of the group of Somalis who arrived in Zambia in 1966, it was revealed that the government of Somalia sent 66 Somali truck drivers to support the Zambian government with road and other infrastructure development.

They further revealed that at first only Somali men were sent, but that they later brought their wives, families, and relatives to Zambia. The group shared that the first group of Somalis settled in Ndola town in the Copperbelt province and later in Lusaka, and then later moved to many other towns in Zambia for residence but also to grow their businesses (Marchand, 2017). These Somali longhaulage drivers facilitated the transportation of copper and petroleum oils between Zambia and the Congo. They came to Zambia to work as expatriate truck drivers within a partnership agreement between the Somali government led by late President Sharmarke and the Zambian government led by late President Dr. Kenneth Kaunda. They thereby contributed to the economic development of Zambia (Simbeye, 2020). Further still, all of the original 66 truck drivers sent to Zambia in 1966 originated from Puntland, and the majority of the Somalis in Zambia continue to be ethnically from Puntland (Herero Universal TV, Video, 2018).

Somali women have also migrated across international borders independently in search of economic opportunities; the majority of women involved in this study were married and were either invited by their spouses to join them or directly migrated and joined by their husbands. Most of the women are employed and were connected to Somalia by sending goods and financial remittances for development and for humanitarian assistance. Somalis mostly visit Somalia to reconnect and socialize with their families and friends; others go for holiday and pleasure purposes, yet others travel for business or investment purposes.

The respondents revealed that the majority of Somalis in Zambia left Somalia because of economic factors such as the search for employment or business opportunities; other respondents cited marriage as the main reason their driver for moving to Zambia. The respondents involved in key informant interviews revealed that entrepreneurship and investment were the main occupations. Somalis in Zambia are very open to investment as revealed in the key informant interviews as well as in the focus group discussions. One of the respondents explained, “I believe that business is one of the best ways to get out of poverty”.

Somali businesspeople in Zambia use their experiences in doing business as qualifications, and this is a useful source of information that others could use upon arriving in Zambia to do business. However, this wealth of knowledge is not harnessed nor documented. In the focused group discussion, it was further revealed that Somalis in Zambia see themselves as different from other migrant groups who re living in Zambia because they came there as expatriate drivers and not as refugees. This was evidenced also by several responses from also the key informants who revealed that there has always been a good diplomatic relationship between Zambia and Somalia, and this had started in the early 1970s. Somalis take pride in the fact they helped build the country of Zambia at a time when its people needed that help. Furthermore, the Somalis also speak proudly of the diplomatic relations that later developed between President Kaunda and Somalia.

These diplomatic relations later resulted in President Kaunda visiting Somalia in Mogadishu in the 1970s when Somalia hosted the continental meeting for the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and in the Somali government providing training programs to the Zambian military in the 1970s. The Somali business community whom this study interviewed, speak passionately about these historical events which ae archived by both Zambia media and the national archives. They believe that they were the steppingstones that led to the current good diplomatic relations between Somalia and Zambia. These good relations manifest in various ways and every now and then a Somali delegation visits Zambia. Sometimes it is the other way around whereby a Zambian delegation visits Somalia, the most recent one in Hargeisa in 2015.

In July of 2018, the former Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khaire visited Zambia to take part in a Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) meeting which was held in the capital Lusaka. This happened after Somalia became the 21st member to be admitted to COMESA. At the summit, final rites were performed under the heading “What Somalia brings”, and the former Prime Minister added final signatures to the accession documents. After this formal attendance, and as a part of his tour, he visited the Somali community and gave a long speech to the Somali community in Zambia about the importance of Somalia’s participation in this trade agreement.

In 2020, a new female Somali Ambassador to Zambia was announced, and the Somali community in Zambia single-handedly renovated the entire Somali embassy with their funds and resources. In terms of their legal stay and legal status, thousands of Somalis have taken up Zambian citizenship either by birth or by naturalization. Everyday civic and diaspora humanitarianism is being strengthened as part of long-established practices where compassion, social obligations, and religion may play central roles such as assisting others in need. These practices of giving are passed down from generation to generation in Somalia. Some Somalis came on their own to Zambia from Somalia to do business as investors, others came from the diaspora such as from the UK, Canada, and the US.

One of the objectives of this study is to explore the precise nature of the Somali business community in Zambia being a long-term group of diaspora people. This is an interesting contrast to refugees who arrived in Zambia in the early 1990s as a result of the civil war. Both groups have established profitable businesses and both are well-integrated into Zambia society, owning mosques, schools, and land, and running diverse businesses such as in the transport sector but also in oil and gas, in real estate and in hotels and restaurants.

Zambia relayed on private companies and operators for its road construction projects some of which were owned by the Italian Fiat Company. This was the same company that recruited the Somali drivers from Somalia with the support of President Sharmarke and Minister Yassin Nuur Hassan of Home Affairs. Minister Yassin would later flee from Somalia as political dissident and settle first in Saudi Arabia and later in Zambia as a business owner.

The first transportation company to be set up in Zambia was called I. Nahar Transport Company in 1967 and it belonged to a Mr. Ismail Nahar. Later other companies such as OHAN transport Company, accrued from the names of Mr. Osman Haji Hassan, an MP in the Somali government at the time, and Mr. Abdirahman Nuur Hassan, the brother to Minister Yassin, would be established. One of the respondents said that “I am one of the 66 drivers whom the Somali government sent to Zambia in March of 1966. We didn’t have hotels or anything. We slept in our trucks, and there were many mosquitos everywhere. Some of the men I came with died on those treacherous roads while on duty. I now live in Kismayo, and I am a businessman here.” The Somali business community in Zambia also actively contributes to humanitarian and other social problems faced by the indigenous Zambians. For example, they provided support when cholera broke out in the country and in 2020 when COVID-19 affected its prisons.

Who is a diaspora and who is not?

Very little research has been conducted to shed light on African diaspora formation within the African continent. The term “diaspora” is disputed. Bakewell (2016), among others, ushers in new and critical thinking about African diaspora and asks are there diasporas in Africa and why have they not been studied enough? Bakewell and Binaisa (2016) studied diaspora practices and relationships and their identification with people, places, and networks on the African continent. They argue that the African diaspora has not been fully studied because this term has not been applied to them. Despite the longstanding patterns of mobility across Africa, relatively few migrant groups have established a diasporic identity that persists into 2nd or 3rd generations. This raises many questions about identifying the formation and the relations between migrants and ‘host’ societies. Diaspora, they argue, should be seen as a ‘social form of groups characterized by their relationship-despitedispersal, and not as a ‘type of consciousness’ or ‘mode of cultural production’ as others have.

For the term diaspora to not to lose its analytical and descriptive value, it needs to be reserved for certain people with distinctive relationships with each other and a homeland. But the reality is that, often times ‘diaspora’ refers to Somalis living in the West and not to the thousands of Somali refugees in neighboring countries. In Somalia the word “diaspora” brings with it great expectations of the transfers of skills and resources from the West for the reconstruction of the country, Kleist (2007).

Africa is portrayed as a continent of people on the move (de Bruijn et al. 2001). There is a danger in looking for diasporas within Africa because we may ‘invent’ diasporas by naming them, e.g the colonial invention of tribes. Cohen (1997) proposes a mainstream definition for the diaspora, arguing that it comprises a strong ethnic community settled away from their home country, with mutual interest, concern, and a collective memory toward a home country. Another view of diasporas comes from Bostrom et al. (2017), who describes diaspora as a range of “transnational communities.” At its most basic, ‘diaspora’ is said to refer to people operating across or outside national boundaries.

Brubaker (2000) studied how the term diaspora has expanded since the late 1980s to imply concepts such as excluded, dispersal, and uprootedness. Studying the diaspora can help in their social construction. The mobility and migration within the African continent have been studied through the lens of refugees whose experiences are documented through the years of civil wars in difficult economic conditions, drought, and famine. Somali migrants have been labeled a “conflictgenerated diaspora” (Bakewell & Binaisa, 2016).

Intra-African migration involves the surge in migration within the continent, with around 19 million moving between the African countries. The surge in the movement is contributed by efforts to enhance regional integration. The African Union defines African diaspora as any people of African origin living outside the continent irrespective of their citizenship and nationality. Still, these people remain willing to contribute to the development of the African continent and the countries of origin. The concept is the movement of the Africans and their descendants to the world in modern and premodern periods.

Can the Somalis in Zambia be considered a diaspora group? Do these communities describe themselves as such? In this case, the boundaries are those of Somalia, and the diaspora includes ethnic Somalis and members of Somali society living or operating in other countries. One feature of the Somali diaspora is that many of its people return to Somalia, whether occasionally or regularly, to visit, do business, participate in local politics, or invest their time and expertise in relief and development (Hammond et al., 2011).

It is important to consider local definition and perception. The Somalis in Zambia don’t define themselves as the diaspora. Halima Mohamoud summed it up: “We are not diaspora, we are Africans in Africa, we belong here.” The Somali community in Zambia attaches meaning to belonging for example distance and geography were mentioned as defining belonging. For example, it was mentioned that Somalia in in Africa and also is not far away from Zambia compared to Western countries. This geographic distance has implications for the level of social distance and attachment with the Zambian community and with Africa in general. But who is to define such concepts as diaspora, humanitarianism, and aid? What does it mean to conceptualize them and what are the implications of naming some groups? These questions are important for this research because this study hopes to contribute to our understanding of the Somali business community who fall under the so-called group of ‘diaspora’ in Africa as aid providers. From an academic point of view, this group is considered to be diaspora because of the descriptions from several descriptions by other researchers. The majority of the Somalis just migrated from Somalia to Zambia they have no proper documentation and have a strong connection with their mother country.

Adamson (2019) also studied how migration states of the Global South manage cross-border migration. She uses a comparative framework to analyze how states differ on balances of power and how they monitor migrants for example the Somali/Ethiopian communities in London. She poses four alternatives; the neoliberal migration policy, the nationalizing migration policy, the developmental state migration policy and the transnational authoritarianism policy. The nationalizing migration policy could apply to this study because many Somalis have not yet been documented by the Zambian government despite their increasing number in the country. Documenting Somalis especially those who have stayed there for a long time could assist in proper monitoring of their business activities.

Studying Somali humanitarian giving through Somali vernacular

Recent scholarship has also highlighted the ambiguity of the term ‘humanitarianism’. Davies (2018: 15) argues that is no general definition for the term humanitarianism and that there is not only one humanitarianism but ‘multiple humanitarianisms’. The mainstream definition of the word ‘humanitarian’ is an action that is intended to “save lives, alleviate suffering and maintain human dignity during and after man made crises and disasters caused by natural hazards, as well as to prevent and strengthen preparedness for when such situations occur”, (Donini, 2010, cited by Davies, 2018). Humanitarian action is governed by key globally accepted humanitarian principles such as humanity, impartiality, neutrality, and independence. However, the concept is not only driven by war or conflict but also by disasterstricken conditions, it also predates war and conflict and has been existing in the life of pre-colonial Africa (Davies, 2018).

Even though Davies’s theorization comes close, it does not fully explain why Somalis help those they don’t know. What other modes can we then use to explain phenomena instead of relaying only on existing western theories? Normative social science approaches lack a culturally appropriate and realistic interpretation of Africana reality and researchers who use them do not take into consideration the historical, social, or contemporary experiences of African people. Somali vernacular humanitarianism could serve the purpose of a non-western research approach and a basic mode of explaining the Somali phenomenon.

To understand Somali diaspora humanitarianism better, one needs to first understand the Somali vernacular of giving and humanitarianism. In the Somali culture, giving and providing humanitarian assistance precedes the civil war and has its roots in pastoralism and the nomadic way of life, in the Somali culture and in the Hadith. Pastoralist families travel carrying very little or no food or drinks for days as they navigate through challenging environments in search of pasture wand water for their livestock. They depend on the brotherly giving of the villages they pass through. This act of hospitality and of giving to one another lays in the long and tradition of helping one another and of providing mutual aid. It is deep interwoven with the culture and the Islamic way of living.

From a cultural perspective, analysis can be sought in, for example, Somali oral literature. Some of the traditional coping mechanisms for crisis response includes helping one another. As such, there are many words, phrases, and proverbs (maahmaah) that describe relations and practices of giving and receiving aid between communities in Somalia. These oral traditions are passed on from generation to generation and are kept alive by the hundreds of Somali proverbs, poems, and songs narrated and sung by Somalis worldwide, making Somalia gain the international title of ‘the Nation of Poets’.

According to the Qaamuuska Af-Soomaaliga or the Dictionary of the Somalai Language written by Professor Cabdalla Cumar Mansuur in 2012, these cultural expressions reference mutual aid, sharing and generosity, through concepts like abaal (indebtedness), wadaagid (sharing/reciprocity), martisoor (hospitality) and faxalnimo (selflessness). Take for example the word tooling which describes milk that has been collected from neighbors and meant to be given to a family whose livestock isn’t producing sufficient milk. The word irmansi means to lend a lactating camel to a family whose animals are not producing milk at all.

More evidence of this can also be read in history and literature books such as in Nuruddin Farah’s 1993 book Gifts whereby a young lady called Yussur tries to share her resentment against portraying western aid as a “gift” to a European aid worker. These two famous Somali proverbs explain why giving and helping each other is important for the Somalis Iskaashato ma kufto – If people support each other, they do not fall; and Gacmo is dhaafaa gacalo ka timaaddaa – Love emerges when hands give something to each other.

In another book, Maps, Nuruddin further goes on to discuss the moral and political implications of gift-giving, arguing that gift-giving from the western world is meant to help affluent countries to incorporate the poorer countries into their sphere or to construct the identities of the impoverished nations. Set in modern-day Somalia, these novels are about how the West treats poor nations like Somalia and other countries that have no choice in transactions that are decided solely by Western NGOs when it comes to the borders between state and non-state support. It’s a cultural definition of what a gift is, or is it a gift or something else, like a lifetime commitment to a benefactor. The institutionalization of how Somali humanitarian principles are organized can generate a basis for methodological approaches that are rooted in Somali people’s realities.

Somali resource mobilization collections are built around cultural and moral values such as reciprocity, and kinship but also faith. Faith plays an important role in giving among Somalis as most of these transnational practices of giving between the Somalis in Somalia and the Somalis in Zambia are embedded not only in these traditions but also in the Hadith. The majority of Somalis are said to be Muslims and they believe in the prophet Mohamed and practice the Hadith which is a record of the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad. Muslims refer to the Hadith as a major source of law and moral guidance, second to the authority of the holy Qurān. The Quran and Hadith repeatedly emphasize the importance of giving sadaqah regularly. Muslims are obliged to give Sadaqah, or voluntary charity, which is a selfless act of one’s gratitude to the Creator and an investment in this life and the hereafter. Respondents cited the following example ‘Give the sadaqah without delay, for it stands in the way of calamity.’

Experiences in Zambia and connection to Puntland

“I am not at home, but I am also not away from it”. A respondent revealed. This is because technology and society have become extremely interlinked. Access to information between people who are far away from each other is not difficult to find. One does not need to physically be somewhere to access information or to be informed about something. Technology allows people to interact beyond the boundaries of location and identities. Somali diaspora advocacy and resource mobilization efforts as practiced by Somalis in Zambia, as elsewhere in the world, is both old and modern, creatively blending centuries-old traditions with current information and technologies.

Social networks exist at various levels, making it easy for Somalis to stay updated about developments in Somalia and to take part in sending humanitarian relief support. Even though they are far away from their home country, they continue to find belonging by joining and participating in the activities of hometown associations which provide instant access to information, solidarity, protection, culture, value, and ethnic orientation. They show great interest in following events as they unfold in their country of birth. One of the respondents from the group discussions explained, “I am in various social media groups. There is one for my family but also one for affairs about Puntland and then I am also in another general group about Somali affairs. So, I am not at home, but I am also not away from it because I am connected to all the news bringers.” They receive information from Somalia immediately because there are members in these groups who reside in Somalia and who report issues as they occur with pictures and videos.

These Whatsapp groups foster new ways of connecting local dynamics and translocal practices, they shape relationships built on trust and sophisticated forms of kinship mobilization. Men and women have different WhatsApp groups and they each mobilize resources differently. For example, business owners prefer to bring over young Somali male relatives from their villages and towns in Somalia and offer them employment as drivers upon arrival in Zambia. These drivers then eventually started their businesses after some time. They would go home to find a marriage partner and later have them brought over to be an establishing family. Somali business owners maintain transnational ties to Somalia through investment as well. Some of them are shareholders of the newly constructed Garacad seaport in the Mudug region of Puntland, and others own greenhouse farm estates in Somalia.

Social media has decreased inequalities of access to socio-technical infrastructure as we are seeing more women, and youth from all clan backgrounds fundraising for a cause. Even Islamic sheiks are TikTok live and Facebook preaching while also mobilizing support. The evolution of Somali (diaspora) humanitarianism has changed over the decades especially with the emergency of the internet that provides real time information to the Somalis the diaspora. The emergency of swift transfer methods also facilitates the process of cash transfers.

Type of assistance mobilized, channeled, and delivered to Puntland

The respondents revealed that they face challenges in mobilizing resources and delivering the mobilized resources to Somalia from Zambia. Among the challenges encountered include; High transaction costs, delays in delivery, and unreliability of methods were mentioned. Lack of trust and difficulties regarding fundraising and sustainability of initiatives in the long-term was also cited, as well as limitations caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and economic hardship. Furthermore, Somalis like many other migrant groups, are subjected to arrests, brutality, and imprisonment.

The respondents revealed that they send relief assistance to Somalia in different forms when disasters occurred. Participants revealed that they helped their families and communities in Somalia by sending financial help, while others sent goods and supplies, technical assistance, or services. Of the 10 respondents interviewed eight revealed that they assisted their families and communities in Somalia by sending them money and only 2 participants supported their communities by providing technical assistance or services. Somalis in Zambia have long-established practices where compassion, social obligations, and religion play central roles. In 2012, the Somali community sent police uniforms to Galkayo. They also took part in supporting Zambians in times of hardship.

The respondents revealed that they sent relief assistance through their families, and community groups. Six of the participants interviewed revealed that they sent their help either individually or as a group. It was also discovered that the Somalis in Zambia play a significant role in providing valuable information to their communities on how to mitigate emergencies and disasters. Some participants revealed that they engaged experts who guided them on the best course of action for the disasters experienced. The Somali business community in Zambia gets information about humanitarian disasters and other crises in several ways. Some use their Facebook pages, others use Somali websites and TVs, while others share information in WhatsApp or Paltalk groups.

Visits to the home country are one of the major manifestations of the transnational linkages maintained by the Somali diaspora in Zambia. Migrants who have strong links with their home country are more likely to visit their home country more frequently than those whose ties with the home country are weaker.

The respondents in both the individual key informant interviews and in the focus group discussion revealed that they frequently visit Somalia at least once a year. Somalis have many transnational hubs globally. There are strong connections with civic groups that are more accessible. Somalis in Zambia are transnational communities, and as such, they connect across transnational linkages. After their arrival, Somalis brought their families and relatives over to look after their businesses. Young Somalis came to Zambia in search of employment. After several years, these youth started their businesses and established families in Zambia. The remittances sent home to their families and relatives help the families left behind with education, livelihood, food, housing, and health access. Somali businesspeople in Zambia are also connected to Somalia, and they have initiated business in both countries. The Somali government invites them to participate in investment meetings, for example, the Puntland Investment Forum. They own investments in Somalia, e.g., Garacad. A Facebook page called “Reer (family) Zambia” has over 600 Somali members.

Though the respondents revealed that they send cash speedily and efficiently, they are hampered by prohibitive transaction costs. As a result of the above prohibitive transactions, the Somalia diaspora in Zambia transfers remittances to Somalia mainly through informal channels. They send cash through friends. The informal channels have lower costs of transactions. Suggestions have been made for the Central Bank of Somali to mandate the establishment of diaspora desks within the local banks to handle diaspora financial remittances at lower cost and without delays to the end-users however that hasn’t happened. The primary reason for remitting is to provide financial support to family and friends, personal investments, and personal obligations. A good number of respondents revealed that they send contributions to the community and social development through faith-based organizations and mosques.

The motivation to give and frequency of giving in the last 20 years

The participants revealed that they give because they have been able to establish businesses to sustain their livelihoods as emphasized by a respondent “I believe that business is one of the best ways to get out of poverty.” The experiences of the Somali diaspora in Zambia are important in understanding not only their connectedness to Somalia but also the challenges they face in sending support. Out of the 10 respondents interviewed, 6 revealed that they send assistance back home because they felt compassion for the needs of their fellow community members. 4 participants were motivated to motivated by family relationships, community solidarity, and religious obligation.

4 participants revealed that they had sent assistance five to ten times in the last 20 years. Another 4 said that they had sent assistance more than 20 times, and two respondents revealed that they had sent assistance between 11 and 20 times, in the last 20 years. The assistance sent by the Somali diaspora has helped victims affected by floods, drought, and hunger. Four respondents revealed that they assisted communities affected by pests and diseases, and 2 participants revealed that they assisted families affected by terrorism and the COVID-19 pandemic. Seven of the participants used Somali remittance institutions to send assistance to Somalia, whereas three of the participants used banks. Remittance institutions were, therefore, the most common means of sending assistance. Several Somali social customs bind Somalis to each other. Others mentioned the 2017 Zobbe Mogadishu attack but also mobilizing for COVID-19 materials.

Understanding Gender in Somali diaspora humanitarianism: Somali businesswomen in Zambia Feminist research has highlighted the possible effects of migration on changing gender relations, increasing women’s power and status, and creating conflicts within transnational households (Wong, 2006). However, it is generally recognized that economic migration improves the socio-economic status of women, which can have notable impacts on countries of origin (Bachan, 2018). The feminist scholarship aims to produce knowledge and contribute to transforming societies (Acker, 1989). In this case, it seeks to empower Somali migrant women by recognizing the increases in their responsibility. This study aims to expand on the need for further research and to expand knowledge of the role that gender plays in Somali diaspora humanitarian support to the home region of Puntland. The study is expected to reveal the connection between humanitarianism and connectedness and business decisions and the role of Somali women’s diaspora migration in Africa. Gender relations undergo negotiations in migration, and it can provide an opportunity for women to pursue new roles and challenge subordinate duties, Schaffer (2013).

Gender roles are changing, and more and more Somali women are taking part in businesses, including types of ventures which previously were dominated by men. One reason for these changing cultural roles is the civil war in Somalia, “and the consequent socio-demographic changes impelled by life in the Diaspora have significantly contributed to shifting gender roles.” The war destroyed the old cultural roles and traditional patterns because many men have to fight and are away from their families and some have died, leaving women in widowhood. They have to take care of their families now and be the breadwinner. These women have had to adopt new gender roles to survive hence killing the idea that only the man has the responsibility of providing for his family.

However, these gender roles can still be challenging for Somali women. The fact that married Somali businesswomen cannot travel a big distance or abroad by themselves for business trips but that they have to be accompanied by their spouse or a close relative is an example of a major constraint for Somali businesswomen. On the other hand, there are also positive developments when it comes to women. Female children in the Somali refugee community in Nairobi are increasingly getting higher education opportunities, while male children are encouraged to take part or start their businesses early, without having the opportunity to get a higher education. But this does still reflect the idea that the man should take care of an income, giving the woman time to get an education.

The inclusion of businesswomen is important because it helps us understand diaspora humanitarianism. The role of businesswomen in developing their home regions and providing humanitarian support is especially significant for the Zambia case because Somali women in Zambia own big and medium-size businesses and companies. These women own trucks, shops, gas stations, restaurants, taxi companies, milling factories, clearance companies, etc. They frequently travel to Somalia and Arab countries to do business and buy merchandise that they sell in Zambia. The women have formed a strong community using social media and advocate for Puntland support.

The lack of knowledge of gender issues can contribute to a lack of sensitivity, understanding, and awareness about gender (in)equality in a Somali context. The available literature on humanitarianism shows that little research has been done on gender and intra-African migration and that more in-depth and careful research is essential. It is critical to understand further the complexities and importance of gender in discussing and addressing humanitarian efforts. Another gap in this literature concerns how gender and women negotiate their positions as diaspora, connectors, and remitters.

4. DISCUSSION, CONCLUSION, AND IMPLICATIONS

The results of this study validated the results of previous research on the impact of the Somali diaspora population and offer insight into how the community operates and sustains itself today. Hammond (2010), Horst (2017), and Lindley (2009) indicate that Somalis view assistance to those in need as an absolute responsibility of the individual as a member of a larger family, clan, community, or umma. The obligation to give is seen as a religious and cultural obligation to assist those who are struck by crisis and contribute to the livelihoods of one’s close relatives.

The study also highlighted the digital tools and technology that contemporary Somalis use to build and maintain the sense of community that drives the continued participation and support of Somalia emigrés. The technology used includes; Facebook pages, Somali websites, and TVs, while others shared the information Via Paltalk or in their WhatsApp groups. It was revealed that all the participants in the study have in one way or the other supported victims of floods, drought and hunger, pests and diseases, terrorism, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of the participants sent assistance because they were compassionate towards the needs of their fellow community members. Others were motivated by family relationships, solidarity, and religious obligation. The digital connections are essential to keeping participants informed and engaged with what’s happening back in Somalia and providing support as needed.

The diaspora of developing countries can be a powerful developmental force for their countries of origin through remittances and, importantly, by promoting trade, investment, research, innovation, and knowledge and technology transfer. The Somali migrant population in Zambia largely comprises first-generation migrants who lived in Zambia as expatriate drivers in the mid-1960s and their descendants. Some came there as refugees following the civil war in Somalia in the 1990s. The Somali population is the second-largest migrant community in Zambia. Previous studies have investigated these diasporas as new actors who can mobilize and deliver faster, as well as the types of support they provide and motivations for doing so. There is also more known about the hardships they face as they send support and the difficulties of earning a decent living as asylum seekers in the West (Hammond 2011).

Research studies on diaspora humanitarianism have contributed to a better understanding of the motivations to give by the diaspora. For example, Hammond (2010), Horst (2017), and Lindley (2009) all indicate that Somalis view assistance to those in need as an absolute responsibility of the individual as a member of a larger whole, whether this is the family, clan, community, or umma. The obligation to give is seen as a religious and cultural obligation to assist those who are struck by crisis and contribute to the livelihoods of one’s close relatives. The support helps them feel that they play an important role in the family and community at large. The participants revealed that the remitters face such great pressures that they often incur great debts to fulfill all their demands. Failure to remit leads to social pressure as expressed by Lindley (2009). Similarly, the use of funds is another source of conflict between the two groups.

Carling (2008) explored why migrants connect to their non-migrant social circles not through a mere feeling of guilt but rather through repaying the gift of commonality as a central moral framework. The article further argues that remittances sent by the diaspora cannot be used for development as the social function and rules of obligations surrounding them do not permit them to be used outside livelihoods and basic needs. Any attempts to divert the support to development initiatives will attract the requirement of the diaspora to remit extra financial support, which the senders cannot meet as they are already overstretched. The action was particularly an interesting line of inquiry for this study and involved examining the diaspora’s social and moral rules around the assistance. We noted that the context of the Somali diaspora in Africa is noticeably lacking in previous studies and not widely reported. In this study, we also observed that there is minimal identification of various diasporic communities within the African continent, and few discussions about their gendered contributions to their home countries, as in the case of Somalis in Zambia.